Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

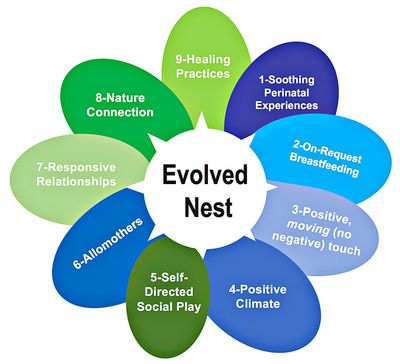

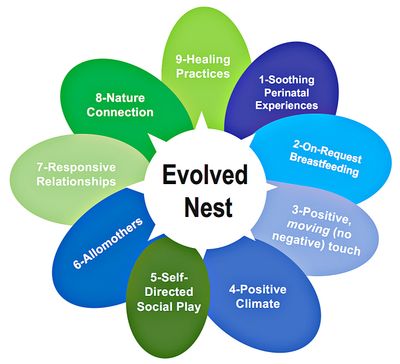

Every animal has a nest for its young that matches up with the maturational schedule of the offspring. Humans too! The Evolved Nest (or Evolved Developmental Niche, EDN, refers to the nest for young children that humans inherit from their ancestors. It's one of our adaptations, meaning that it helped our ancestors survive. Most characteristics of the evolved nest emerged with social mammals more than 30 million years ago.

The USA is experiencing a decline in child and adult physical and mental wellbeing, with for example, everyone under age (in 2018) 55 at a health disadvantage compared to other advanced nations (e.g., National Research Council, 2013).

The baselines for normal childrearing have shifted in the USA. Many people seem confused about what children need and what appropriate childrearing is. With little attention to our deep history, it is easy to believe anything. Parenting seems more about how little of children’s needs can be provided to children and still have them reach adulthood intact. At the same time, children’s health and wellbeing have deteriorated (OECD, 2009; UNICEF, 2007), young children’s aggression and psychotropic medication levels are on the rise (Gillam, 2005; Powell, Fixen & Dunlop, 2003), and anxiety and depression are at epidemic levels for all age groups (USDHHS, 1999).

With only 25% of the brain fully developed at birth, the first three years of life encompass the most critical time period for human neural development. As Niehoff (1999) describes, for optimal functioning later, the young brain “must be protected during development from factors that impair growth, damage neurons, or interfere with the formation of synaptic connections” (p. 274). During the first two years and the introduction of the child’s systems to the surrounding environment, the immune system “uses early experiences to elaborate a repertoire of antibodies that will determine future vulnerability to infectious disease” and sets the thresholds for stress response used for a lifetime (ibid, p. 274).

The stress response system must be protected from “either collapsing or overheating” due to challenges it is not yet prepared to handle (ibid, p. 275). It is apparent that US children are not being protected from early toxic stress and its subsequent effects on neural and immune functioning (Shonkoff et al., 2012).

Every animal has a nest for its young that forms part of an extra-genetic inheritance corresponding to the needs and maturational pace of offspring (Gottlieb, 1991; Oyama, Griffiths & Gray, 2001). Humans evolved to have the most helpless newborns and the most intensive caregiving niche. Childrearing practices consistent with the human nest were practiced for over 99% of human genus existence and still are in some indigenous cultures. Intensive caregiving in early life includes nearly constant touch, extensive breastfeeding, and free play with multi-aged peers as well as positive social support for the mother-child dyad and multiple adult caregivers (Hewlett & Lamb, 2005; Hrdy, 2009). All these caregiving practices are correlated with physical and mental health outcomes, but also with social and moral development.

Human development is biosocial: healthy bodies, brains and sociality are formed from family and community life experience in early life. If brain and body system thresholds are established suboptimally in early years—not by trauma, but simply by not providing care that children evolved to need, then children may not reach their potential. They may show underdevelopment of concern for others, a sense of social responsibility, and global citizenship.

IMPORTANCE OF THE NEST

Human Immaturity at Birth

Human babies are born early. For several months postnatally relative to other primates, human babies share characteristics of fetusesrather than infants of other primates (Trevathan, 2011). For example, in terms of bone growth, a human baby’s ossification of phalanges is similar to that of a gestational macaque and does not reach macque neonate levels for several years. Apes have developed cranial plates whereas the human neonate’s are mobile to facilitate birth and do not settle for several months afterwards (Schultz, 1949). Among primates generally, the brain of a newborn is half the size of an adult’s brain. Using primates as a model, humans should be born at 18 months of age (Trevathan, 2011). Although all apes are born earlier than the typical primate, humans are the most immature, with only 25% of the brain developed at full term birth.

There are several periods in life when brain development is most malleable: gestation, birth, the first five years after birth, early adolescence, emerging adulthood and therapy. But the most influential periods for human development (and those where the effects have been noted more closely) appear to be during gestation and the first five years of life. With 25% of the brain in place at birth, the first five years of life encompass the most critical time period for human neural development. They encompass the “genesis of the nervous system, the road-building time when neurons are born and axons navigate the chartless expanse of the embryonic brain to found synapses,” (Niehoff, 1999, p. 274). For optimal functioning later, the young brain “must be protected during development from factors that impair growth, damage neurons, or interfere with the formation of synaptic connections” (Niehoff, 1999, p. 274).

By the end of the first year, the brain reaches 60% of its adult size. Brain volume will be perhaps 75% complete by age 3, 90% by age 5. Volume isn’t everything though. Myelinization (glial cells facilitating communication among neurons) of several brain systems occurs in the first years of life (e.g., somatosensory, auditory) with the visual system completed by 4 months of age (Bronson, 1982). We can see from the early-developing visual system that there is a critical period for its optimal development. If a child has an uncorrected lazy eye or kittens are prevented from seeing during the sensitive period, there is no going back to redevelop the capability. Similarly across the brain the way things are connected or not, how many receptors there are, the thresholds for their activation, have sensitive periods for optimal development. All matter too for a well-functioning brain. These, along with volume, are influenced by early experience. So, although development per se proceeds in an evolved order, timing and sequence, how well it goes depends on external factors, primarily caregiving. And with each layer of development, the range of options narrows, as early developing systems form the foundations for later-developing systems.

Why does the evolved nest matter? Early years are when virtually all neurobiological systems are completing their development. As mentioned, there are sensitive periods throughout the first five years of life in which particular caregiving is expected by the maturational schedule of the child. When expected care is not forthcoming, development will be less than optimal. The Evolved Nest is the baseline for species normal care.

And it is a matter of justice for young children. The concern for young children and their caregivers is rooted in a concern for justice. To notreceive human nest in early life can be perceived as an injustice to a child, with serious ramifications for the child’s future.

State of USA Today

Child mental and physical wellbeing have been on the decline for over 50 years in the USA, the wealthiest nation on earth. People under the age of 60 score at or near the bottom on multiple health indicators than citizens in 16 other advanced nations.[1] The USA has heightening epidemics of depression, anxiety, psychosocial and health problems at all ages.[2] Because humans are holistic creatures, attachment, sociality and moral capacities have also been declining (e.g., empathy, moral reasoning).[3] Avoidant attachment has been increasing along with narcissism, both of which undermine social and citizenship capacities.[4] Sociopathy has become a cultural phenomenon.[5]

Although there are likely multiple causes, we can surely point to one basic cause with converging evidence from across the human sciences: Early life toxic stress.[6] Recent research is tempering views that deficits from poor early care can be easily outgrown; many cannot be.[7] In fact, an increasing amount of converging evidence across animal, human psychological, neurobiological and anthropological research demonstrates the later vulnerability of brain and body systems among those with poor early care.[8]

What is needed for healthy child development? The evolved nest.

Converging research is demonstrating that human development is biosocial: healthy bodies, brains and sociality are formed from early experience provided by family and community. Every animal has an evolved nest (evolved developmental niche; EDN) for its young that forms part of an extra-genetic inheritance corresponding to the needs and maturational pace of offspring.[9] Humans evolved to have the most helpless newborns and the longest maturational schedule of any animal.[10] Human child-raising practices, rooted in social mammalian parenting over 30 million years old, evolved to accommodate these factors and were practiced for over 99% of human genus existence and still are in some indigenous cultures.[11] The evolved nest in early life includes soothing perinatal experiences, extensive breastfeeding and positive touch, free play with multi-aged peers and nature connection. Human variations observed among hunter-gatherer societies also include positive social support for the mother-child dyad and multiple responsive adult caregivers.[12] All these caregiving practices are correlated with health outcomes, but also with social and moral development.[13]

Justice for Children, Societal Wellbeing

Our concern for young children and their caregivers is rooted in our concern for justice. To notreceive the Evolved Developmental Niche (EDN), Evolved Nest, in early life can be perceived as an injustice to a child, with serious ramifications for the child’s future. If brain and body system thresholds are established suboptimally in early years—not by trauma, but simply by not providing care that children evolved to need, then children may not reach their potential or become cognitively and socially underdeveloped. For example, children who do not receive supportive parenting early are less likely to behave prosocially.[14] They are more likely to be self-centered and uncooperative.[15] While such children may sometimes function well enough as adults, holding down jobs and raising families, we are interested in caregiving environments that foster optimal development. Specifically, we are interested in the development of proactive concern for others—an orientation that includes a sense of social responsibility, global citizenship and prioritizing care for others, including the natural world.

REFERENCES

[1] National Research Council (2013). U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

[2] e.g., UNICEF (2007). Child poverty in perspective: An overview of child well-being in rich countries, a comprehensive assessment of the lives and well-being of children and adolescents in the economically advanced nations, Report Card 7. Florence, Italy: United Nations Children’s Fund Innocenti Research Centre; Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2009). Doing better for children. Paris: OECD Publishing.; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (2013), How’s Life? 2013: Measuring Well-being, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264201392-en

[3] e.g., Konrath, S. H., O'Brien, E. H., & Hsing, C. (2011). Changes in dispositional empathy in American college students over time: a meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15, 180-198.

[4] Twenge, J. & Campbell, R. (2009) The narcissism epidemic: Living in the age of entitlement. Free Press.

[5] Derber, C. (2013). Sociopathic society: A people’s sociology of the United States. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Press.

[6] Lanius, R. A., Vermetten, E., & Pain, C. (2010). The impact of early life trauma on health and disease: The hidden epidemic. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; Shonkoff, J.P., Garner, A.S. The Committee on Psychosocial Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, and Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, Dobbins, M.I., Earls, M.F., McGuinn, L., … & Wood, D.L. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress.Pediatrics,129, e232; Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score. New York: Penguin.

[7] (e.g., Karr-Morse, R., & Wiley, M.S. (2012). Scared sick: The role of childhood trauma in adult disease. New York: Basic Books.; Lupien, S.J., McEwen, B.S., Gunnar, M.R., & Heim, C. (2009). Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition, Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 434-445.

[8] Felitti, V. J., & Anda, R. F. (2005). The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Kaiser Permanente.

[9] Gottlieb, G. (2002). On the epigenetic evolution of species-specific perception: The developmental manifold concept. Cognitive Development, 17, 1287–1300.; Oyama, S., Griffiths, P.E., & Gray, R.D. (2001). Cycles of contingency: Developmental systems and evolution. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

[10] Montagu, A. (1968). Brains, genes, culture, immaturity, and gestation. In A. Montagu (Ed.), Culture: Man’s adaptive dimension (pp. 102-113). New York: Oxford.

[11] Hewlett, B.S., & Lamb, M.E. (2005). Hunter-gatherer childhoods: evolutionary, developmental and cultural perspectives. New Brunswick, NJ: Aldine.

[12] Hrdy, S. (2009). Mothers and others: The evolutionary origins of mutual understanding. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

[13] e.g., Narvaez, D., Wang, L., Cheng, A., Gleason, T., Woodbury, R., Kurth, A., & Lefever, J.B. (2019). The importance of early life touch for psychosocial and moral development. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 32:16 (open access). doi.org/10.1186/s41155-019-0129-0; Narvaez, D., Woodbury, R., Gleason, T., Kurth, A., Cheng, A., Wang, L., Deng, L., Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E., Christen, M., & Näpflin, C. (2019). Evolved Development Niche provision: Moral socialization, social maladaptation and social thriving in three countries. Sage Open, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019840123l Narvaez, D., Wang, L, & Cheng, A. (2016). Evolved Developmental Niche History: Relation to adult psychopathology and morality. Applied Developmental Science, 20(4), 294-309. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2015.1128835; Narvaez, D., Gleason, T., Wang, L., Brooks, J., Lefever, J., Cheng, A., & Centers for the Prevention of Child Neglect (2013). The Evolved Development Niche: Longitudinal effects of caregiving practices on early childhood psychosocial development. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28 (4), 759–773. Doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.07.003

Narvaez, D., Wang, L., Gleason, T., Cheng, A., Lefever, J., & Deng, L. (2013). The Evolved Developmental Niche and sociomoral outcomes in Chinese three-year-olds. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 10(2), 106-127; Narvaez, D. (Ed.) (2018). Basic needs, wellbeing and morality: Fulfilling human potential. New York: Palgrave-MacMillan; Narvaez, D. (2016). Embodied morality: Protectionism, engagement and imagination. New York, NY: Palgrave-Macmillan.

[14] Kochanska, G. (2002). Mutually responsive orientation between mothers and their young children: A context for the early development of conscience. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11, 191-195.

[15] Sroufe, L.A., Egeland, B, Carlson, E.A., & Collins, W.A. (2008). The development of the person: The Minnesota study of risk and adaptation from birth to adulthood. New York: Guilford.

Copyright © 2024 The Evolved Nest - All Rights Reserved.

An educational initiative of the award-winning nonprofit Kindred World.

Don't miss the latest blogs, research, insights, and resources!